When I moved to the Netherlands from the United States at the end of 1997, I lived for three months in a hotel next to the Bijlmerbajes, the most notorious prison in Amsterdam, before settling in to my new home of Zandvoort aan Zee, a beach resort village on the coast outside of Haarlem. Obviously, some alienation was inevitable in a new country. Confronted with a foreign language, a different culture, unfamiliar money (at that time, still the Dutch Guilder), trying to make friends, and the constant upheaval that comes from missing the countless tiny givens I had unconsciously relied upon in the States, I tried to find my way.

While I often delighted in the surprises and curious disorientation that culture shock brought with it, there were so many small differences between the United States and the Netherlands (and many larger ones too), that I often found myself in need of help. From my very first day in Zandvoort, an English saloon on Haltestraat called Williams Pub was the center of my social world, and the place I went to find answers for my most basic needs. In fact, without Williams Pub, I likely would have failed in my attempts at integration in those early days.

Even shopping for groceries was daunting. Familiar product brands were absent, food had Dutch names, and knowing where to find even the most mundane items was difficult. Simply finding ingredients for some cornbread, a staple of southern American cuisine, was a challenge. Conferring with locals, I discovered that baking soda was called natriumcarbonaat (or zuiveringszout) in Dutch, and naturally, it could be found at the pharmacy! Cornmeal required a visit to a Turkish grocery store in Haarlem to get “mihlama.”

Of course, I wasn’t the only foreigner who struggled. I met an English “likely lad” by the name of Barry, a chippy who had just arrived in Zandvoort from Old Blighty. Like many of the English who haunted Williams Pub, Barry was from Cumbria. While grocery shopping, he had encountered the same dilemma as I, with disastrously comical results. One evening, as a group gathered for a session in the back garden of Williams Pub, he told us his story.

His desire had been simple. All he wanted was a bit of brekkie. He went shopping at the local grocers, guessing as well as he could to select the products he needed. He bought what he thought were eggs, oil, bread, butter, milk, and beer.

With his haul, he got down to business one Saturday morning, fighting through the hangover provided by Williams Pub the night before. Pouring some oil in a pan and heating it up, he admitted to us that he detected an odd smell while that was going on, but thought little of it. He fried up his eggs, toasted and buttered his bread, and poured a glass of milk.

His first bite of eggs revealed that he had just fried them in vinegar. Disappointed, he turned to his toast, only to discover he had buttered it with lard. Not all lost, he grabbed his glass of milk, and upon his initial sip, Barry realized he had purchased buttermilk. Obviously baffled, he explained to us that he had taken the milk carton with the red label, just like his mom always did in England.

Remaining incredulous, Barry continued his story. As respite in his woe, he had popped open a bottle of Amstel beer. After downing six, and feeling nothing, he examined the label a bit more closely only to discover he had selected alcohol-free, Malt beer. Barry didn’t remain in the Netherlands for long.

And for me to remain, adjusting to life in the Netherlands required constant vicissitudes. Besides solving grocery mysteries, I also quickly discovered that a bicycle was a necessity, a mode of transportation used every day, not just for weekend jaunts when one felt sporty. In America, I had a mountain bike, more attuned to the hilly terrains of Missouri and Texas, where I had lived before moving overseas. However, bringing the bike with me had not been practicable — nor affordable — on my flight. So, I looked around Zandvoort.

I was a bit shocked by the prices I saw. To get a new bicycle of any quality, I was faced with an outlay of around $800-$1000. And, on a salary of only 60,000 Guilders per year, which was approximately $33,000, I was bringing home around $20,000 after taxes, or about $1670 per month. Rent for my tiny one-room apartment in Zandvoort was $600 per month. A new bike was a luxury I simply could not afford. Even used bikes were upwards of $300-$400.

Finding myself once more at Williams Pub, I imbibed an ice-cold, half-litre of freshly tapped Groslch (at $3, a bargain), while contemplating my predicament. An acrid cloud of tobacco smoke hung in the pub, recharged constantly by dozens of smokers. Sitting in the haze, occasionally punctuated by a pungent influx from the back garden outside, I lamented my bike quandary to one of my Dutch friends. “No problem,” he said, and proceeded to explain that I just needed go to Amsterdam, and then find my way to the back of Central Station.

There, he assured me, I could find drug-addled junkies who sold stolen bicycles, hoping to scrape together enough money to support their heroin habits. Moreover, he advised, I needed to look for the junkie whose hands were trembling the worst. I would get the best deal from him since he needed his fix most desperately. I could probably get a bike for $10-$20 I was told.

Now, I never actually followed through on the advice. But I also never forgot the vivid images conjured in my mind of shaking, desperate junkies hustling hot bicycles in the murky underworld behind Amsterdam’s otherwise gorgeous train station. Thankfully, another peculiar Dutch practice came to my rescue and delivered a bicycle into my hands — for free.

Having moved to the country carrying only two duffel bags — one filled with clothing, and the other with compact discs and books — besides needing a bicycle, I was also in dire need of furnishing my apartment. But living on the wages I made at the time, I could not afford much furniture either. Again, the pub provided a solution.

As strains of Monaco’s “What Do You Want From Me?” sha-la-la’d their way from the speakers at Williams Pub, and cold Grolsch welcomed us once more, my friends assured me that they could help me find some furniture and would “give me something I can rely on, far away from the life that I once knew.” Happening once per month, an event called “grofvuil” would occur again soon and provide me what I sought, or so they promised me.

On the evening of grofvuil the following week, the raw underbelly of Dutch society was laid bare as I wandered the streets of the village and stared in wonder. It was becoming clear that there was much more to this country than just wooden shoes, waffles, windmills, and water.

Grofvuil is a peculiar practice that the Dutch take for granted. In essence, once per month, anyone can take old possessions no longer needed or wanted and throw them out to the street. The next day, a swarm of junk-cleaner-uppers employed by the city governments drive along the streets in trucks and pick it all up. However, the night of ejecting the unwanted goods is the fleeting moment when needy immigrants such as myself could benefit from the event. In this case, one man’s trash is indeed another man’s treasure. And, the hoard of somewhat dismal, grimy riches I discovered was astonishing. But I had to be quick. The next day, the bounty would disappear.

Throughout the village, on most streets, I found couches, chairs, tables, lamps, washing machines, mattresses, old flooring and all manner of discarded household goods. And, that was just in Zandvoort. There is a Dutch photographer who has made a name for himself picking through the dubious treasures found in the different neighborhoods of Amsterdam on the nights of grofvuil, staging rather remarkable still-life photo compositions from his finds.

Thanks to grofvuil, I was able to furnish my apartment from the flotsam and jetsam of the streets of Zandvoort. Yes, it was a hodgepodge of mismatched items, and my rooms were a jumble of curiosities and furniture in varying states of decrepitude. But I no longer needed to sit on the floor, and I could eat my meals at a table. I even found an old television, and it worked.

The dates of grofvuil were indelibly recorded in my calendar, and I became adept in knowing where the finest rejectamenta could be found. Sanford and Son would be envious (or, for our British readers, Steptoe and Son). Now, if only I could find a bike.

A couple of months later, I did. I spied a bicycle in a heap of rubbish, thrown out into an alley around the corner from my local pub. The chain was frozen fast with rust, the tires were flat. But it was complete, and better yet … a Batavus, a high-quality Dutch bicycle make. My skills at bike repair had been forged in the foundry of Missouri mountain-biking many years before, and it was quick work to get the bike up and running. 4 guilders for chain oil and 5 for a tube repair kit, I soaked the chain loose and patched the tubes. My liberation was complete. Now, I could transport myself around town, or bike through the dunes from Zandvoort to Haarlem anytime I pleased.

As the years went by, I continued to assimilate. Each day, taking the train to work, I read the newspapers left behind by other travelers. I immersed myself in the Dutch language, and the news of the country. I still have a shoebox full of oddball articles I ripped out of the papers, ones that I thought were particularly flaky and worthy of retention. I read about the fat-bottomed cow competition where farmers pitted their bovines one against another and judges selected the winner with the nicest, plumpest, roundest ass (complete with photo of winning cow butt); petty crimes such as the burglar who got shot in his buttocks by an old lady wielding a hunting rifle when he tried to escape her house with his ill-gotten gains, crawling headfirst out of a window; and another article about the mountainous multitude of bicycles dredged from the canals of Amsterdam each year.

While reading the article about dredging the canals, a thought occurred to me. I could help make a difference. I conceived of an idea that could solve a couple of problems at the same time. Remembering the story of the junkies who sold stolen bicycles behind Amsterdam Central Station, and having read about the heaps of bikes pulled from the canals of the city each year, it dawned upon me. What we needed were Scuba-Diving Junkies!

The idea was simple. Instead of spending tens of thousands of guilders to dredge the canals and pull up the bikes, we needed to teach the junkies to scuba dive! They could scour the canals and keep them bike-free, and all of the bicycles they found would be theirs to sell. It was genius. This would also reduce the amount of bikes the junkies stole from innocents to support their drug-habits. A true win-win. And, in a liberal country such as the Netherlands, and particularly, in a heterodox city like Amsterdam, it just might work.

Filled with enthusiasm, I rushed to Williams Pub, and started sharing my idea with my friends. But they were skeptical and tried to temper my zeal. What if the junkies didn’t want to scuba-dive? I had already thought of that, I told them. The answer was clear. We will add nitrous-oxide to the scuba tanks as an incentive, keeping them motivated and happy while they dive. But what if a junkie drowns? Well, while undoubtedly sad, certainly it was also one less junkie to worry about, and they were dying from overdoses anyway, right? Scuba-diving would surely be less dangerous than heroin.

But then, they asked, why would the Amsterdam City Council be interested in starting such a programme? I pondered that for a moment. Well, I could imagine word getting out, and tourism increasing with people from around the world curious to come watch the scuba-diving junkies at work, bringing additional tax revenues to the coffers of the city. What the Changing of the Guard was to London, the Scuba-Diving Junkies could be to Amsterdam! Moreover, junkies who survived would also have a valuable skill and perhaps be able to turn to a legitimate life.

Now, I am sure, fair reader, you already realize that I was never truly serious about promoting such a ridiculous scheme as the Scuba-Diving Junkies, and that it was mere fodder for our frivolous conversations at Williams Pub as we laughed and bantered over our cold Grolsch beer, one-upping one another with tall tales. However, I still sincerely believe that had I submitted my plan, Amsterdam would have at least considered the idea, though it is highly unlikely they would have ever approved and implemented the scheme.

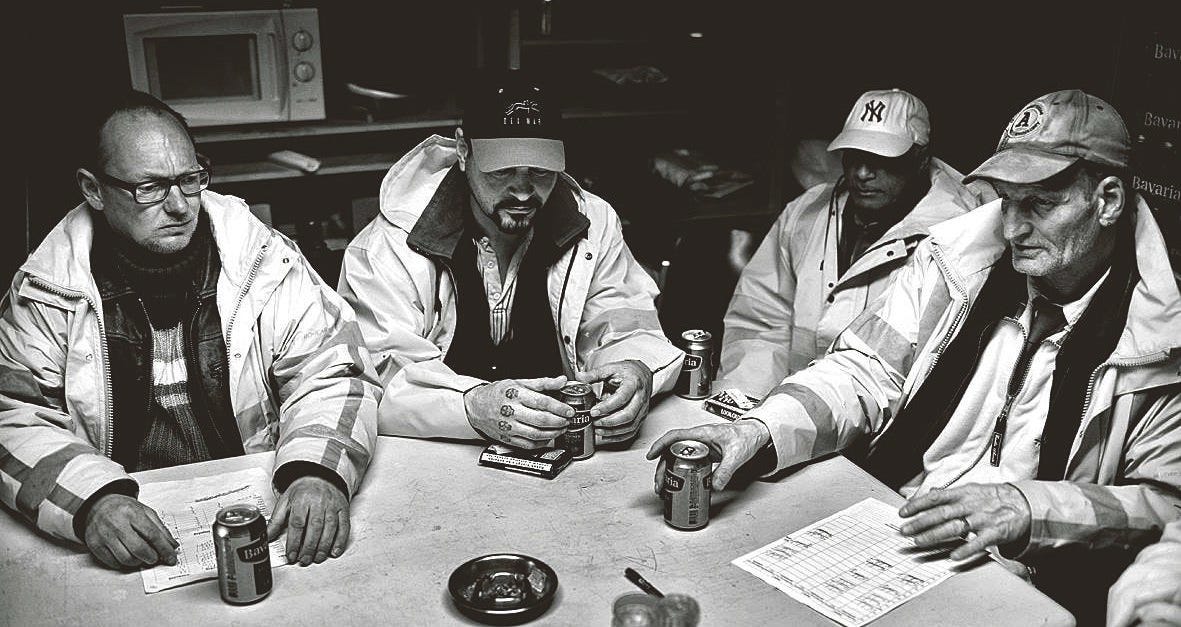

And yet, you surely remain dubious of whether there ever really would have been a chance. Remember my shoebox of strange newspaper articles? At one point, there was quite a controversial story in the papers concerning alcoholic, homeless vagrants in Amsterdam who hung out in Oosterpark. The park suffered from the trash they strew around, and other noxious messes left lying about (I’ll leave the details of that to your imagination). Moreover, the unpredictable behaviour of the men created a nuisance. An organization in Amsterdam called the Regenboog Groep (Rainbow Group) decided to try a radical new approach to cleaning up the park, while also helping these less fortunate members of society.

Ideas were considered. Budget was allocated. Finally, an approach was agreed that involved engaging the shiftless men themselves to clean up the park. In return for their work, they would receive unusual compensation. At 9am sharp, they started their day, receiving two cans of beer as an appetizer, then the cleaning began. At noon, they received a lunch and two more cans of beer. Then as the day concluded, another beer or two and some cigarettes or rolling tobacco topped off the day of tidying up, along with a cool 10 euros in cash. This approach was met with much enthusiasm by the alcoholics, and the park was quickly in order. As news spread that the city was buying the labor of pitiful bindlestiffs with alcohol, the outcry was predictable, but the experiment survived. According to one article:

“Now they drink at set times, they are less quickly drunk and better accepting of correction. It works: the secret lies in the beer. Currently, the problems in the park have decreased, confirmed by the local city government.” [translation from the Dutch by author].

Now, how could you have doubted that my proposal of Scuba-Diving Junkies would have been seriously considered by the city of Amsterdam? An actual success story of payment in beer for services rendered indicates that my idea would surely at least have been put to a vote, likely failing by only the slimmest of margins.

Who knows? Maybe a slim chance remains. The city still spends a significant amount to dredge the canals each year. Perhaps a city council member will read this story and put forward a plan. Viva la Scuba-Diving Junkies!