Jack Clemens, Human Fly

“A sign painter by trade, but a human fly by choice.”

The Flies

The “Human Fly” phenomenon in the United States reached its pinnacle in the mid-1920s. In the decennia since the advent of steel construction in the late nineteenth century, cities around the country had steadily erected higher and higher buildings, which attracted a peculiar breed of daredevil, commonly referred to as a Human Fly. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, a veritable swarm of Human Flies descended upon downtowns across the United States. Determined to scale the tall structures of these cities without harnesses, ladders, ropes, nets or helps of any kind. Human Flies cheated death and defied gravity, to the thrill of spectators in cities from coast to coast. However, death did not always take kindly to being cheated, and the law of gravity often exacted revenge. The list of Human Flies who tumbled to their deaths is long.

A nickname sometimes used by Human Flies was “Jack,” extracted from the term “steeplejack.” But a Human Fly was not the same as a steeplejack. Defined as “a craftsman who scales buildings, chimneys, and church steeples to carry out repairs or maintenance,” a steeplejack fulfilled a community need or business demand.

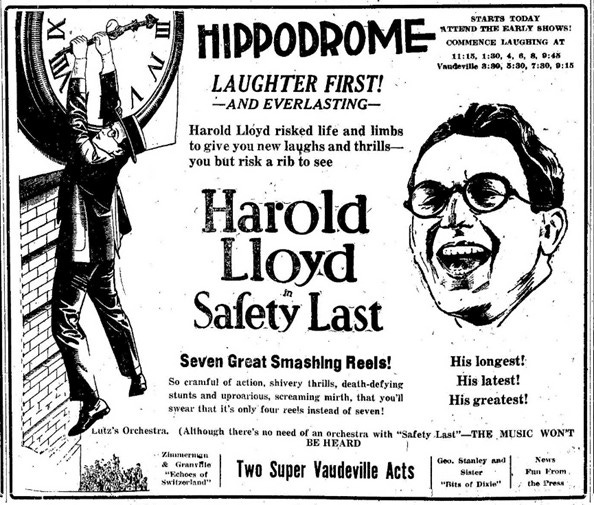

The Human Fly, however, was a thrill-seeker, a showman. Many became famous, featured on front pages of newspapers across the United States, or even on the silver screen. Harold Lloyd was inspired to film his 1923 classic Safety Last, with its iconic scene of him hanging precariously from a clock, after watching Bill Strother climb a building in Los Angeles in 1921. Enlisting Strother to star in Safety Last together with him, Lloyd immortalized such nimble skill in his film.

Other well-known Human Flies were Henry Roland, Charles Miller, George Polley, Fred Cimino, and, perhaps the most famous, Harry Gardiner. According to Gardiner, President Grover Cleveland himself coined the phrase in 1895, dubbing him the “Human Fly,” after watching Gardiner scamper up a 150-foot (46m) flagpole in New York City.

Jack Clemens, as he called himself, was a Human Fly considerably more obscure than these others, and of far lesser reputation, but not for lack of ambition. And, unlike many of his fellow Flies, Clemens really was a steeplejack, pre-equipped with the skills necessary to become a Human Fly seamlessly when he assumed that role.

The temptation to turn to a career as a Human Fly was strong. As one observer noted, “the steeplejack is a man who acts the part of the human fly for the easy money that goes with the courtship of death.” Perhaps by becoming a Human Fly, Clemens was also simply trying to escape the trouble he invariably got himself into while his feet were on the ground.

Hailing from Joplin, Missouri, Jack Clemens began his career in vertical theatrics during the second half of the 1920s, in the waning days of the Human Fly craze. Reflecting his bona fides as a steeplejack, he abandoned his given name and made rightful claim to the nickname Jack. At the start of his career, he still used his initials, and styled himself S. V. “Jack” Clemens. As his career progressed, he whittled it down to just Jack.

Cheating death, and run-ins with the law, became regular pastimes for Jack. The “human” part of the moniker Human Fly particularly applied to him, especially when he was drinking. And, in the era of Prohibition, when Jack began his career, having a drink was fraught with risk.

Early Years

Ostensibly, Jack was bestowed with the name Steve Virgil Clemens when he was born on April 28, 1905, to James Austin Clemens and Mary “Mollie” Rebecca Fowble, into a large Mormon family in Joplin, Missouri. His father was the Superintendent of the Joplin Waterworks, and the President of a local School Board. Jack was the fifth child in the family. He had red hair.

The multitude of Clemens children attended the Grand Falls School in Shoal Creek, just south of Joplin. Jack sang for the school Christmas shows. By the time he was 14, he had to compete for his parents’ attention with 12 brothers and sisters. Perhaps this is one of the reasons Jack turned to his death-defying stunts early in life.

“Clemens began human fly antics when but a boy. There was a standpipe at the Joplin waterworks, his father works as chief engineer, which had the boys bluffed because it reared up in the air about 135 feet [41m]. Jack climbed the standpipe one night and when he got to the top he gave the boys an extra thrill by standing on his head and wiggling his feet. His dad didn’t approve of such a daredevil feat and took Jack to task for it, so he took his meals standing for the next several days.”

The Missourian, November 12, 1931.

Although he was punished for this act by his father, apparently strenuously enough that he could not sit down for a few days, it provided Jack the attention he craved.

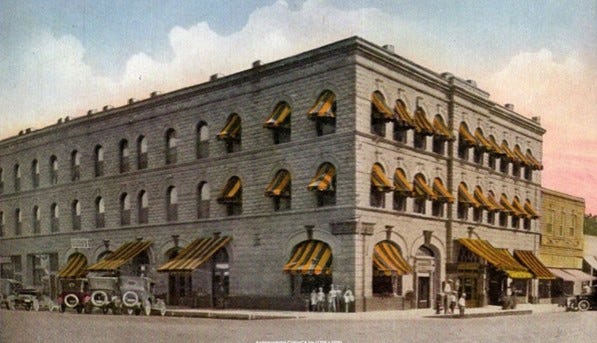

In 1915, when Jack was 10 years old, the famous Harry Gardiner brought his Human Fly act to Joplin. On May 10, 1915, Gardiner enthralled 5000 spectators gathered to watch him climb the Connor Hotel, an 8-story structure that presented little challenge to the famed Fly from New York who had scaled much taller buildings. Nonetheless, it was an impressive feat. And, even if Jack was not on hand to see Gardiner climb the hotel, he surely heard about the spectacle, fueling his own dreams of becoming a Human Fly. Moreover, the success of Gardiner’s visit to Joplin in 1915, prompted him to return to the city the next year for another set of highly-publicized climbs, providing Jack an additional opportunity to be inspired.

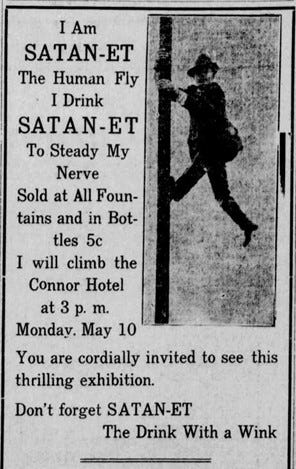

When arriving in a city, some Human Flies would seek financial sponsorship from local merchants and businessmen. In return, their escapades would draw people to the city center where they would patronize the local stores. Other Flies passed the hat, hoping for 50 or even 100 dollars for their trouble. Established Flies with broad reputations like Gardiner had no need for piecemeal funding from merchants and could rely upon licensing their personas to pitch various businesses and brands to consumers. And that is exactly what Gardiner did in Joplin with Satanet, a nationally advertised “drink with a wink” from Norfolk, Virginia.

In his future pursuits as a Human Fly, Jack Clemens established a regional reputation, but never the type of national renown achieved by Gardiner. As such, Jack typically followed the practice of gaining sponsorship from local merchants, and no doubt passed the hat from time to time.

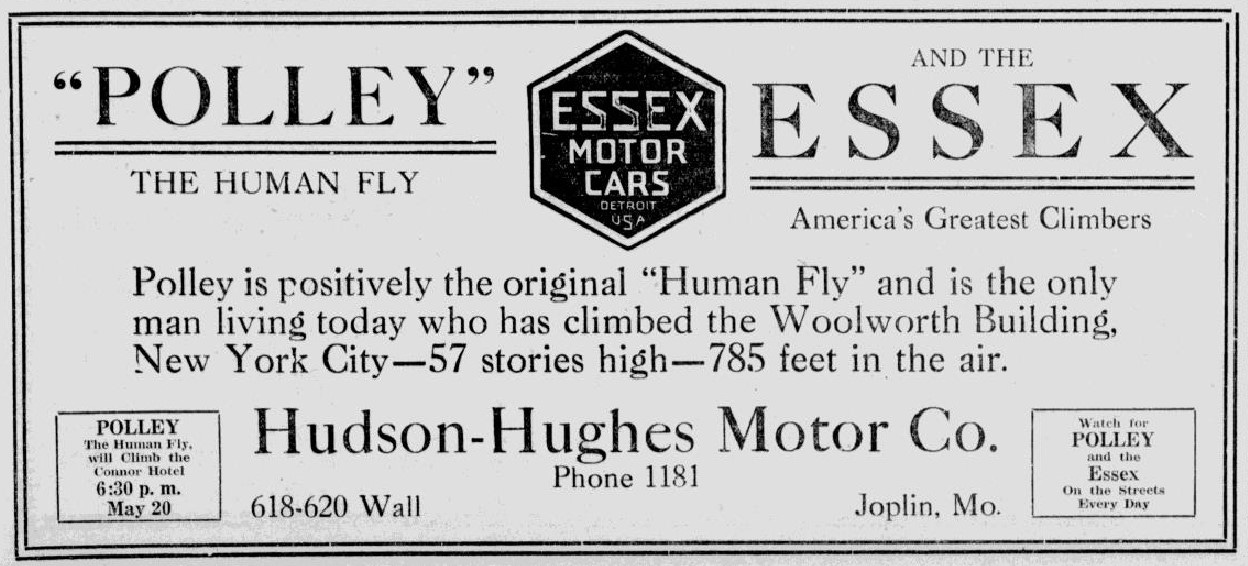

George Polley was nearly as famous throughout the country as Gardiner, and also tried his luck in Joplin. Arriving in May 1920, Polley duplicated some of the same feats as Gardiner, such as climbing the Connor Hotel. Also a magician and friend of Harry Houdini, Polley enjoyed a significant national reputation himself and was able to sell his name to the Hudson-Hughes Motor Company in Joplin, purveyor of Essex Motor Cars. They used Polley’s fame to advertise their dealership in the Joplin Globe while he was in the city. Jack, now 15 years old, took notice. Later in life, he would claim that he started climbing at 16, implying that the Polley visit may have convinced Jack to follow this line of work.

Besides the Human Flies that would arrive in Joplin from time to time, other depictions of their deeds testified to the glory and prestige that could be achieved climbing buildings, and doubtless encouraged ambitious young Jack. Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last premiered in Joplin at the Hippodrome on April 29, 1923, the day after Jack’s 18th birthday. Aspirations of finding fame as a Human Fly only grew after the film came to town.

While Jack’s own climbing exploits would later be his vehicle for some adulation and moderate fame, a glaring lack of self-control also brought him considerable infamy. A born thrill-seeker, Jack led an extremely fast-paced existence from an early age and accelerated to breakneck-speed during the last ten years of his short life. Along the way, he also employed his abundant charisma at attaining what he pleased.

Fledgling Fly

Jack left his childhood home while still a teenager. Maybe he felt insignificant and overlooked living in such a big family, or perhaps he simply wanted to live his own life outside of the boundaries placed upon him by his Mormon parents.

On January 14, 1924, Jack married Zoe Z. Zentner, a local girl from the Shoal Creek area of Joplin, where the Clemens family also lived. Jack was still only 18, and Zoe, born Christmas Day 1904, had just turned 19. But when they applied for their marriage license at the Newton County Courthouse in Neosho, Missouri, where they were also married, both avowed that they were above 21 years of age.

Little is known of their life together, but their union did not last long, and Jack’s chosen profession clearly contributed to the failure of his marriage. His desire for thrills made him a natural candidate for working in high structures, and he worked as a journeyman steeplejack by joining the Painters Union. A newspaper article later recalled, “the heights called to the boy and … he has been travelling over the country painting steeples, flagpoles and smokestacks too hazardous for others to paint.”

Jack and Zoe divorced on November 20, 1924, after being married for less than a year. Jack’s peregrinations as a steeplejack and Human Fly had left Zoe alone in Joplin. According to an “Order of Publication” run in the Web City Sentinel in the month preceding the granting of divorce, Zoe complained that Jack had “absconded or absented himself from his usual place of abode,” and further claimed “indignities” as grounds for ending their marriage.

As part of the divorce grant, Zoe’s reclaimed her maiden name. In an article on November 20, 1924, the Carthage Evening Press reported on 69 divorce cases that had been granted that day, including “Zoe Clemons [sic] from Steve Clemons, with restoration of former’s maiden name.” After they split, Zoe remained single for the rest of her life. She worked as a salesperson for the Gateway Creamery in Joplin. When she died in 1967, Zentner was the name used on her death certificate. Her marital status was recorded as “divorced.”

Jack shook off his first marriage and moved on without Zoe in 1925. He was living in Joplin at 2424 Bird Avenue, where one of his neighbors was Fred Overall, a local grocer with whom Jack would go into business in 1929. Their personal and professional relationship would faulter however after Jack’s conduct placed them on the wrong side of the law.

The Great War, which had ended as he turned thirteen, fascinated Jack. He built a collection of WWI relics, including a 75mm French ordinance he loaned to an American Legion Exhibition at the Memorial Hall in Joplin in September of 1925. But, more stimulating pursuits than collecting dusty relics of war beckoned. Even as Jack began building his reputation as a Human Fly, he also became notorious in Joplin as a hellion.

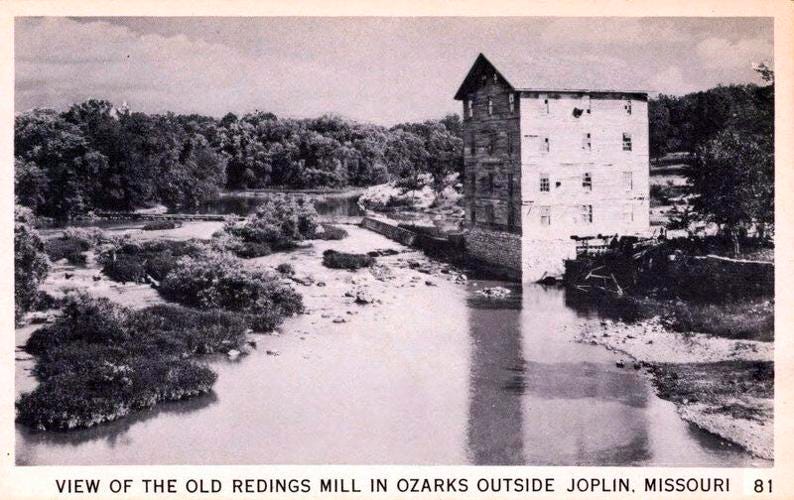

On Sunday evening, November 8, 1925, Jack was on a joy ride along Redings Mill Road just south of Joplin with Fred Fuller, Lacey Francis Lanham and a group of three women. And while no proof can be provided that they were drinking, what happened next, together with Jack’s later struggles with alcohol, seems to point toward this. They all just narrowly escaped dying that night.

At 10pm, they approached the bridge across Shoal Creek, when the driver suddenly lost control of the car and it plunged over a 20-foot (6m) embankment, rolling three times. Miraculously, no one was killed. Only one of the girls was seriously hurt. Hazel Wilson fractured her femur and was taken to the hospital, and Dorothy Davis had minor lacerations to the back of her head.

Fortuitously, Ruby Franz, Lacey Lanham, Fred Fuller and Jack Clemens escaped unharmed. All declared that they had been “driving at a moderate rate of speed.” It would not be Jack’s last serious car accident.

In 1926, Jack got married again, this time to Opal Gladys Williams. Opal was born on New Year’s Eve 1906, in Brady, Oklahoma, to John A. Williams and Ida Belle Kimball. John was a farmer and a teamster. Opal was only 9 years old when he died. When she met Jack, Opal was working as a “saleslady” and lived in Joplin with her mother in a bungalow at 1511 S. Pearl.

As they headed out to Neosho together to obtain a marriage license, Jack was 21, and Opal 19. They had a June wedding and hoped for prosperity and happiness. Jack and Opal were married on June 3, 1926. But Jack didn’t want to settle down right away and start a family just yet. He was determined to become a famous Human Fly.

While nothing is known of his exact whereabouts in 1927, it appears that Jack was already traveling widely performing as a Human Fly, while also plying his trade of painting high structures and signs. A new highway, Route 66, ran straight through Joplin and was established on November 11, 1926, just a few months after Jack and Opal got married. Route 66 provided Jack a ready means to reach new locations with his Human Fly exploits. Indeed, many of the cities where Jack would be reported to have performed during his career lay along this famous road.

The direct access to Chicago made possible by the new highway also allowed Jack to work there for the Eagle-Picher Lead Company as a steeplejack early in his career. He would also do jobs for Eagle-Picher in Joplin from time to time in the coming years.

Even as Jack was desperate to travel and build his career, in the summer of 1927, Opal let Jack know that a baby was on the way. So, he settled back into Joplin. By the end of the year, they were living at 404 North Connor Avenue with Opal’s half-brother Earl White. As 1928 began, Jack and Opal welcomed a baby daughter into their lives, born in Joplin on January 27, 1928. They named her Virginia Belle Clemens. But Jack was soon back on the road again.

Apparently, he continued to come and go from Joplin in 1928, traveling while trying to build a name for himself as a Human Fly. By summer that year, Jack had already become sufficiently well-known in this role, and absent from Joplin frequently enough, that a visit he made back home to his parents was noteworthy. On July 24, 1928, the Joplin Globe reported his return under the banner “‘Human Fly’ Here on a Visit.” The brief mention commented on Jack’s work as a showman. “Clemens travels over the country, engaged in exhibition climbing.” Apparently, Jack spent little time in Joplin by then. The Globe also revealed that “he has never appeared in an exhibition here.”

This small article from 1928 is the first known reference to Jack Clemens as a Human Fly. In the 1930s, many such stories would be printed about Jack's checkered adventures.

By September of 1928, Opal’s brother Earl had moved on from 404 Connor out to the Chitwood area of Joplin. Jack was back home again and … for the moment, portraying himself as a properly domestic husband and father. He took Opal to visit Earl and his wife at their new home. However, Jack’s family-man façade soon vanished.

Outcast

In March of 1929, Jack’s younger brother Delno Clemens took off for Los Angeles together with Eugene and Raymond Moffett. In those days, Route 66 ran all the way to Santa Monica, and while it had not been completely paved yet by 1929, still offered travelers one straightforward road from Chicago, directly through Joplin, out to California.

Jack would not be far behind his brother in heading west. But whereas Delno’s departure had been celebrated with a going-away party hosted by friends, Jack was chased out of town by the authorities after running afoul of the law.

On August 17, 1929, five months after his brother left for California, Jack was arrested. Having paused his Human Fly pursuits, he was living at 1325 ½ Main Street, and worked at 1425 West Seventh, running a “Pig Stand” owned by Fred Overall, his former neighbor from Bird Avenue.

A Pig Stand was essentially an early incarnation of the Sonic type of drive-ups we know today, complete with car-hops. The shops primarily sold BBQ pork sandwiches. But Jack was using Overall’s Pig Stand as a front for illegal alcohol sales as well. His secret was soon discovered.

On August 17th, Jack Clemens and Fred Overall were apprehended by order of the Prosecuting Attorney Russell Mallett for selling “a quantity of intoxicating liquor.” Justice was swift. Two days after he was arrested, Jack was arraigned and posted $200 bond. His trial was held the next day.

Indicating that Overall was likely not part of Jack’s alcohol scheme, the charges against him were dropped. With Prohibition the harsh law of the land, Jack was handed down a six-month jail sentence, but was paroled out of the state in lieu of having to serve time.

The Fly barely avoided the web of prison that had threatened to ensnare him. But to do so, he had to flee. Exiled from the state where he was born, Jack took Opal and little Virginia Belle, only nineteen months old, and left Missouri.

Likely, this is the moment he decided to change his name. Jack's troubles with the law had received wide-spread attention in Joplin. His arrest, arraignment and trial, as Steve Clemens, were covered nearly daily in the paper. But this was not the type of notoriety he had envisioned. He had received the scorn of public opinion. He had disappointed his parents. And Opal was now faced with a journey into the unknown with their baby.

Jack left Joplin in disgrace in September 1929. But he still longed for the adulation of the crowds that turned out to watch him risk his life when he climbed, doubtless, some of them anticipating calamity.

And a month later, calamity is exactly what the spectators witnessed who gathered to watch Fred Cimino, famous Human Fly, rappel head-first down the nearly completed Civic Opera in Chicago, a 44-story building downtown on Wacker Drive. On October 15, 1929, Cimino was on the radio drumming up publicity just before his descent, telling his listeners, “Good-by, everybody. Here I go, head first. This is my business. I love it.”

Making it halfway down the building to the 23rd floor, Cimino lost his footing and fell about 280 feet (85m) to his death, landing on two 17-year-old boys at street level who were watching him perform, killing one. As if symbolizing the impending financial disaster about to hit the United States, two weeks after Cimino hurtled into the ground, the Stock Market crashed, ushering in the Great Depression.

Jack had his own money problems. To solve them, he was intent on performing like Cimino, while somehow avoiding the same demise. As Jack dragged his wife and baby farther and farther away from Joplin in the autumn of 1929, surely Opal wondered how she had ended up in this dilemma. Not much is known about their exodus. But they headed for the western United States, and they may have travelled as far as California like brother Delno.

Later reports indicate that Jack scaled at least one building in Los Angeles, penultimate western destination of Route 66, but the timeframe for this is not known. Additionally, Jack had a friend in Riverside, California, a Joplin man named David A. Dunn who had left Missouri for the Golden State in about 1923. Also pointing to a California sojourn, it appears that Jack may have picked up a manager for his act during this period of exile, a man from Oakland named “Doc” Fisher.

Even as the days of 1929 dwindled and 1930 began, Jack still had several months on his parole before he could return home to Missouri. By March of 1930, he was in Utah with Opal and little Virginia Belle, heading back east on their way to Denver, Colorado. We can assume that as a member of a Mormon family, even with his wayward ways, Jack would have also visited Salt Lake City while traveling through the Beehive State. As they approached the border with Colorado, his reputation as a Human Fly caught the attention of a local newsman in Jensen, Utah. Jack was still going by his given name at this point.

“Steve Clemens the human fly and painter by trade passed through Jensen on Wednesday enroute to Denver, accompanied by his wife and baby,” the Vernal Express reported. Whether he had actually scaled buildings in the West during this period cannot be said for certain, but considering the reporter’s ready acknowledgement of Jack’s standing as a Human Fly, it seems probable that he did.

Upon arrival in Denver, Jack, Opal and Virginia Belle settled in for a time at 562 Santa Fe Drive, in what is now the “Arts District" of the city. They stayed long enough to be recorded there in the 1930 Federal Census – and, importantly, also long enough to wait out Jack’s banishment from Missouri. On April 2, 1930, the census listed him as an unemployed painter of signs, which may imply that Jack’s gravity-defying activities were paying the bills at this time.

Return to Missouri

Four months later, Jack was ready to leave Denver and return to his home state. He was also ready to cast off his given name. His banishment had been the wake up call Jack needed. Ambivalence left behind, he laid ambitious plans to launch his career as a Human Fly in earnest. By the end of July, he had crossed the border back into Missouri and was in Kansas City sizing up various downtown buildings for climbing potential. However, until he could arrange for a Human-Fly-payday, Jack had a family to support and he found work at the Ritzy Rag Company at 4310 East Fifteenth Street in downtown Kansas City.

Working a day job while drumming up publicity for his Human Fly exploits, Jack and his family likely found refuge with Opal's mother Ida Belle, who had by then remarried and moved to Kansas City from Joplin. She and her new husband William Turnow, purveyor of second-hand furniture, had a home at 614½ Independence Avenue. No doubt Grandma Ida Belle was thrilled to see baby Virginia Belle again.

Jack did not dawdle in concocting a fresh Human Fly scheme for Kansas City. Whereas Salt Lake City had offered the promise of paradise for a Mormon, for an aspiring Human Fly, the skyscrapers of Kansas City offered a land of milk and honey. With a population of 400,000 inhabitants in 1930, Kansas City was already massive, and continued to build impressively tall buildings, even during the Great Depression. From the moment he arrived, Jack had been using his steeplejack’s calculus to identify an appropriately imposing building in the city to conquer, and soon got word to the press of his intent.

Even outside of Kansas City, stories of Jack’s plans began spreading widely. 170 miles away, under the headline “Joplin Human Fly to climb hotel in Kansas City,” the Springfield Press in southern Missouri reported on his ambitions in an article on July 30, 1930. “S. V. ‘Jack’ Clemons [sic], Joplin, Mo., has found ‘just the building’ to strut his stuff. He will be ready in a day or two … to climb the 11-story Bray hotel,” they promised. Whether to aggrandize his climb, or purely from an honest mistake, Hotel Bray was incorrectly reported to be 11 stories tall. It actually rose to 9 stories, and still does. Nonetheless, it was the same height as the Connor Hotel in Joplin that was mastered by both Harry Gardiner and George Polley when Jack was a teenager. And even at two stories less than reported, it would be no small feat to conquer Hotel Bray.

Of course, Jack had jumped right to work getting the word out to the Kansas City newspapers. At the Kansas City Journal-Post, Jack found a willing partner to tell his story. Beginning July 30, 1930, a series of articles leading up to his proposed climb of Hotel Bray was run in the Journal-Post. In fact, from the number of photos and stories produced in the short span of a week, it is clear that Jack spent considerable time at the offices of the Journal-Post promoting himself. He even utilized their building at 22nd & Oak for climbing practice. As a proper representative of Human Flydom, naturally, Jack was attired in dress clothes while photographed climbing, adhering to the precedent set by Harold Lloyd in Safety Last.

According to the Journal-Post:

“S. V. (Jack) Clemons [sic], Joplin, Mo., is only 24 years old, but he has to hunt for thrills. He’s in Kansas City now, and has just found a building to climb. Not with the aid of a ladder or rope or any of the other contrivances ordinary persons use in scaling high walls. That’s too tame for Jack. He uses finger tips and toes. For Jack is a ‘human fly.’”

Kansas City Journal-Post, July 30, 1930.

Two days later, Jack had set the date and time to master Hotel Bray, and informed his selected media outlet. The Journal-Post ran the tantalizing headline:

The article provided the public with the details of Jack’s impending climb of Hotel Bray at 1114 Baltimore in downtown Kansas City. They reported that he would begin his ascent of the building at 12:30 on Tuesday, August 5, 1930.

“Clemons, in a search for thrills, came to Kansas City seeking a building that would tax his ability. Other human flies had told him he could not climb the Bray, he said, and he will attempt Tuesday to prove them wrong. Hand over hand he will go from the street level to the top floor of the hotel, depending on his fingertips to take him where others would use ladders.”

Kansas City Journal-Post, August 1, 1930.

Jack and the Journal-Post continued to hype his climb in the paper, with yet another article on Sunday, August 3, two days before his stunt was to occur. Accompanied by a photo of his “stubby fingers,” Jack philosophized on the relative danger of different types of climbing in the story. And, in order to entice the public into gathering to watch his antics, Jack also described “disastrous” falls from buildings and flagpoles.

“These hands belong to S. V. “Jack” Clemons [sic], human fly, who will climb the Bray Hotel Tuesday noon. It is the strength in his stubby fingers, he says, that enables him to scale the walls of buildings in the towns he visits while working in his profession.

‘The wall of a building doesn’t move,’ he said, ‘and if a man’s fingers don’t slip, there is no danger. But, painting flagpoles really is dangerous. Go up say 100 feet and get within four feet of the top of the pole and you’ll find it swaying in the wind until you can hardly keep your place. And a 100-foot fall from a flag pole will prove as disastrous as the same fall from the side of a building. I’d rather perform as a human fly any day.’”

Kansas City Journal-Post, August 3, 1930.

Then, on August 4, 1930, the day before Jack’s climb of Hotel Bray was to occur, the Kansas City Journal-Post ran one last teaser for its readers. Again, precipitous “plunges” to the ground were invoked to titillate the public and goad them into turning out.

“As if the climb up the hot stone wall will not be enough, Clemens has added an additional thrill. When the top floor is reached, the fly will go inside the building and leap through a window, depending on his skill to catch the window sill on the way out so as not to plunge to the street.”

Although other steeplejacks had warned Jack that it was not possible to climb the Bray, he was out to prove them wrong. And, with his promised leap out of a window at the end of his climb, he was upping the ante. Jack firmly believed in his ability and strength, anticipating that scaling the building would catapult him to widespread fame, and set the course for his career as a Human Fly.

Jack be nimble

Built in 1915, with a mere 25 feet of frontage Hotel Bray is sometimes called “Kansas City’s skinniest skyscraper.” Like other contemporary hotels downtown, the Bray was designed in the Dutch Revival Jacobethan style, and, except for its height, would not seem out-of-place if set down in Amsterdam in the Netherlands today. In recent years, the hotel has been nominated for the National Register of Historic Places. But, when Jack was preparing for his climb, Hotel Bray had only just claimed its place in the Kansas City skyline fifteen years before.

August 5, 1930, had finally arrived, and Jack took his position in front of Hotel Bray. Of course the Journal-Post was there to document the occasion. Any worries Jack may have had that a crowd would not materialize to watch him “strut his stuff,” were completely set aside on the day of his ascent of Hotel Bray.

The various articles in the Journal-Post had cunningly worked their magic on the public, and an estimated crowd of 3000 arrived to see Jack climb. Many of the onlookers undoubtedly anticipated that at some point, should Jack’s “stubby fingers” fail him, they might see a small figure quickly hurtling back earthward, growing larger and closer until they heard the inevitable thud of impact. As they say, it is not the fall that kills a man, it is the sudden stop at the end. From far above, a photographer for the Journal-Post snapped a photo of the massive crowd gathered in front of Hotel Baltimore across the street from Hotel Bray, waiting in the noonday heat for the event to begin, eager for the “cold chill” they had been promised.

A blistering heatwave was baking the Midwest in July and August that year, with temperatures breaking 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38°C) in many cities. Kansas City was only slightly cooler, with the temperature reaching 98 degrees (37°C) on the day of Jack’s climb. As the crowd continued to grow in anticipation of the spectacle, a buzz of conversation echoed off the surrounding buildings. “Will Jack succeed? Or, will he fall to his death as Cimino had in Chicago the year before?” The excitement was palpable. As the clocks declared that 12:30 had arrived and it was time to get started, the crowd stilled, enthralled as Jack’s ascent of Hotel Bray began.

Following the standard set by Harold Lloyd in his film Safety Last, of course Jack had dressed to impress for his climb. He wore a starched white shirt, suit pants, white dress shoes, black necktie, and styled his red hair combed neatly to one side. Considering the sweltering heat, Jack can be forgiven for abandoning his suit coat, unbuttoning the collar of his shirt and loosening the knot of his tie. Whether from the extreme heat, or from nervousness, or likely both, Jack wiped the sweat from his brow and began his climb.

Quickly up past the marquee, he traversed the second floor, and then continued to move steadily upward. Inch by inch, floor by floor, Jack made his way skyward as the crowd craned their necks to watch. When he reached the eight floor, the photographer was waiting to snap a shot of Jack in action, his visage betraying intense concentration. The photograph was expertly angled to reveal the mass of people below.

Triumphantly, Jack reached the top of Hotel Bray, putting Kansas City and the rest of the country on notice. Jack Clemens was a Human Fly of note. The series of articles in the Kansas City Journal-Post, culminating in a breathtaking success, was his first substantive coverage from a major American city. It was just the sort of publicity Jack needed to ramp up his career … if he could keep himself out of trouble.

After Jacks’ stunning subjugation of Hotel Bray, his appetite for the spotlight and the adulation of the crowd only increased. Like Harry Gardiner and George Polley before him, Jack was ever more determined to make a name for himself through the courtship of death. And, Kansas City seemed like just the place to grow his reputation. Corrupt local Political Boss Tom Pendergast was just putting the finishing touches on his “Ten Year Plan” for further augmenting the skyline of the city, while also gearing up his efforts to gain control of lucrative Federal Works Projects Administration (WPA) funding in Kansas City. Additionally, a 50 million dollar bond would be passed in 1931, ushering in a massive wave of construction which would see the Jackson County Courthouse, Municipal Auditorium, and the country’s tallest City Hall all rise up to compliment an already impressive cityscape.

The opportunities for an aspiring Human Fly in Kansas City were seemingly endless. But, Jack appears to have put his aspirations in the city on hold … perplexingly, just as he was making headway in his career. His self-destructive tendencies regrettably resurfaced when Jack decided to make a visit to his hometown at the beginning of 1931, no doubt to celebrate the success of his latest climb. But his celebrations always seemed destined to devolve into dissipation and disaster.

Jack went back to Joplin, and got back into trouble. On the evening of January 4, 1931, he was out on Redings Mill Road again, where he and five others had been involved in a dramatic, potentially fatal car accident back in 1926. Driving with James Hervey of Bird Avenue where Jack had lived in years gone by, again they lost control of the car, it went into a ditch and flipped over. A newspaper headline reported, “‘Human Fly’ Slightly Injured in Car Accident.” Jack walked away bruised up, but with only a cut on his lip. The report stated that the accident occurred because the “steering mechanism became impaired.”

Knowing of his past run-in with the law over alcohol, his record of reckless driving, and two more egregious incidents involving alcohol soon to come, likely Jack was the “steering mechanism” that was “impaired.” But, he shook off the accident and counted himself fortunate that he had not been more badly injured, and also that the police had not been involved.

Rising Again

Perhaps concerned that his presence in Joplin put him at risk for renewed scrutiny from law enforcement, particularly with his name in the newspaper again, Jack quickly returned to Kansas City. He laid plans to make scaling buildings for a living his primary occupation, with sign painting and work as a steeplejack ever more an afterthought.

In March 1931, Jack had a new plan. Intent on besting his previous climb of Hotel Bray the year before, Jack prepared himself to confirm the old adage: “what goes up, must come down.” Turning to a new outlet for his publicity, this time Jack engaged the Kansas City Star to portray his peculiar talents.

On March 16, 1931, the Star prominently featured a photograph of Jack climbing the front of Hotel Bray, under the headline “Elevators are not necessary to this Human Fly.” The article revealed that Clemens would give an “exhibition of his ‘human fly’ tactics” that coming Saturday, March 21, 1931, the first day of Spring. They revealed his plans to transcend the previous year’s climb by scaling up Hotel Bray, and then … go back down again.

A photograph accompanying the announcement was cleverly composed. Captured in action almost halfway up the hotel, Jack again deployed a meticulously calculated charm offensive on the city. In the photo, of course he exemplified the public perception of the Human Fly established by Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last. Jack was shown dapperly dressed in a suit, his red hair oiled, parted, and combed neatly to the side. This time Jack welcomed the warmth of his suit jacket in the cooler weather of March.

The accompanying text described the scene:

“If S. V. ‘Jack’ Clemens fails to pay his room rent at the Hotel Bray, the management will find it rather difficult to keep him from entering the room for his baggage. Clemens at present has a room on the ninth floor of the hotel and the photographs above show him climbing the side of the building to his room.”

Intending to double the vertical distance he had traveled in his previous climb, Jack would have to ascend and then descend Hotel Bray to top his spectacular deed of the year before. While no additional reports of this climb have been found thus far, in his relentless quest to defy gravity and cheat death, there is little doubt that Jack once more thrilled a downtown crowd.

Fisticuffs

Unfortunately, no matter how eager he was for fame and fortune as a Human Fly, Jack consistently fell to temptation and allowed alcohol to control him. Less than five months after his second climb of Hotel Bray he got himself into yet another mess.

In August of 1931, Jack brought his Human Fly act to Wichita, Kansas. Apparently, he was unsuccessful in getting an article printed about his intended climbing show. Nonetheless, his presence still inevitably made the papers.

While nothing has been discovered about an actual climb, we do know that Jack was out carousing in Wichita on Sunday evening, August 2, with Doc Fisher, of Oakland, California, as well as two other men and two women. The group stole off into an alleyway in the quadrant of Market & Main and 2nd & 3rd to pass around a bottle of hooch, likely one of many they emptied that night.

Although Prohibition still prevailed, and stealth was required to avoid detection, nonetheless, a drunken “war” broke out amongst those gathered, with Doc Fisher getting the worst of it. The ruckus they made quickly attracted the attention of residents in the area who called the police.

As the fighting raged out of control, someone picked up a brick and cracked Doc Fisher in the head, fracturing his skull.

According to the Wichita police:

“Fists were flying freely before officers arrived. The three-cornered hole in Fisher’s forehead gave rise to the theory that the corner of a brick hit the man.”

The other combatants quickly fled the alley, leaving Jack pummeled and bloody and Doc with a grisly crater in his broken head. When the police finally showed up, Jack blithely told them that “his manager was giving him a work-out.” Both Jack and Doc were rushed to St. Francis Hospital. Jack’s injuries were deemed superficial, and he was released into police custody. They promptly arrested him for “being drunk and disturbing the peace.”

Somehow avoiding another prosecution and a potential jail term, Jack shook it off and moved on, as he always did. He returned to Kansas City, to Opal.

See No Evil

Undiscouraged by his setback in Wichita, Jack still had big plans. After he returned to Kansas City, he came up with a new gimmick to get his story in front of the public. Reportedly no longer satisfied with the simple thrill of climbing buildings without any safety measures, Jack had now decided that defying gravity did not require him to be able to see. His confidence in his ability to climb had only grown and he intended to make his next attempt blindfolded. To advertise his latest innovation, Jack returned to the Kansas City Journal-Post to make his case for attention.

In an article run in the Journal-Post on September 10, 1931, Jack shared his new plans. “This human fly racket is getting kinda tame. I’ve doped out a new stunt which should knock ’em cold,” Jack told them. The article went on to state, “Clemens’ new stunt is to go up the side of a building blindfolded. He declared today that no one ever had attempted the feat before.” Apparently, Jack had been practicing his blindfolded climbing skills for a couple of months prior to his proposed climb.

Having decided upon the Labor Temple at 14th and Woodland to stage his latest spectacle, Jack set the time and date of his sightless ascent at 5:30pm on September 11th, 1931. He would perform his act in order to “advertise the Building Trades Council,” Jack told the Journal-Post. He was “donating his services to the … council because he is a member of the painters’ union.” Even so, Ray England, president of the council, “obtained a release from Clemens, which frees the Building Trades council from any liability for accidents to him.” Again, the Journal-Post had reminded the public that severe injury, or even death, lurked behind every Human Fly. Nevertheless, Jack lived to climb another day after surmounting the Labor Temple.

In Kansas City, with its ever-upwardly-surging skyline, Jack could readily find buildings to conquer. But, he also wanted to keep his traveling show alive and bring his act to new markets. To do so, he needed a new manager. Apparently, the alleyway brawl in Wichita had convinced Doc Fisher to find better prospects elsewhere. Longing to travel out West again, Jack needed someone with a car.

Cass County Conquest

On November 8, 1931, a couple of months after his disastrous visit to Wichita and his subsequent redemption on the Labor Temple, Jack placed an ad in the Kansas City Star to find anyone willing to promote his act, and most importantly, a “promoter with car” to take him where he needed to go.

Evidently, someone answered the ad, because three days later, Jack was about 40 miles south of Kansas City, in Harrisonville, Missouri, county seat of Cass County. This time, he behaved himself and didn’t garner attention with drunken shenanigans. Brandishing the photos from the Kansas City Journal-Post and the Kansas City Star showing him scaling Hotel Bray, Jack convinced The Missourian, a local newspaper, to run a front-page article under the headline, “Human Fly will perform Saturday.” Alongside another article triumphantly declaring, “Two More Chicken Thieves Captured,” the piece recounted how Jack had “‘conquered’ the Bray Hotel, Kansas City,” and promised, “Joplin man will furnish many thrills Saturday in scaling outside of Courthouse.”

Not wanting to be outdone, the Cass County Democrat also ran a front-page piece about Jack’s intended climb under the headline, “‘Human Fly’ to Scale Courthouse.” His legitimate claim to the nickname Jack was also showcased in the article, revealing that “for several years [he] was employed by the Eagle-Picher Lead Company of Chicago as a steeplejack.”

Sizing up the Cass County Courthouse in Harrisonville, Jack opined to The Missourian, “the courthouse is much more difficult” than Hotel Bray, “although not so high.” He also declared he might climb the building blindfolded, “and that no one had ever tried that feat before.” Moreover, to partially finance his work in the time-honored manner of the Human Fly, Jack also agreed to climb the flagpole and paint it on the way down, “if the business men will ‘kick in’ sufficiently to interest him,” the article declared.

However, with widely-reported, high-profile mishaps involving Human Flies in other cities, such as the death of Fred Cimino in Chicago, the County also had some requirements of its own for Jack. Like the Building Trades Council a couple of months before, in agreeing to let him climb the courthouse, Cass County also demanded he sign a waiver releasing the County and Courthouse from any responsibility “in case he loses his hold and falls to the ground.”

The report in The Missourian concluded expectantly, “Clemens comes here recommended as a fellow who does the very thing he says he will do. So, we’ll see Saturday afternoon at three o’clock.”

Although it was already mid-November, on the day he was to ascend the courthouse, Jack was met with mild weather, a welcome stroke of luck. A crowd gathered to witness the spectacle. Attracted to Harrisonville by the newspaper coverage, people came from miles around to watch Jack climb the courthouse on November 14, 1931. Harry Swaar and his family even travelled 20 miles from Main City, Missouri, and according to the Cass County Democrat, they “witnessed S.V. (Jack) Clemens, ‘human fly,’ of Joplin, Mo., scale the courthouse, which he did very successfully.”

Jack’s climb was big news. No less than thirteen local papers from other towns in Missouri reported on Jack’s success, each article describing how he “climbed to the third story roof [and] from the roof, Clemons [sic] climbed the tower.” The Cass County News was rightfully impressed: “Harrisonville was entertained last Saturday afternoon when Jack Clemens of Joplin ‘human fly,’ scaled the outside of the court house without aid of rope or ladder” — a resounding triumph. And most importantly, Jack had remained on the outside of a courthouse … at least for now.

Revitalized by his achievement, Jack resolved once more to keep himself out of trouble. But how long would he be able to steer clear of temptation? He must have made promises to himself, and also to Opal and Virginia Belle. But promises are so easily abandoned when resolution is dissolved by alcohol.

Unseasonable weather had been kind to Jack on the day of his climb in Harrisonville, the 14th of November, with the temperature a balmy 64 degrees Fahrenheit (18°C). Two days later, it was freezing again at only 19 degrees (-7°C), the paltry high temperature for the day. Winter was setting in.

However, before Jack could go in search of warmer climes for his climbs, he and his new manager made another stop in Butler, Missouri, just 30 miles south of Harrisonville. There, both the Butler Daily Democrat and the Bates County Democrat announced that Jack would climb the Inn Hotel on Thursday, November 19, 1931, “just after the football game.”

Jack was also touting his blindfolded climbing routine again, but had not yet decided if he would actually perform the stunt. The newspapers reported, “he is not sure, it depends on circumstances.” The articles concluded by assuring the citizens of Butler, “If you want to get a thrill come out and see him.” Regardless if Jack blindfolded himself when he climbed the hotel, by that point the chilling temperatures were impossible for him to ignore.

Sunny California promised warmer weather, more predictable for scaling the outsides of buildings. With ready transportation now arranged with his new manager, Jack was soon out on Route 66 again, on his way back to the West Coast.

Going back to Cali

Thus began a series of journeys in the first five months of 1932, to climbing locations in California, Oklahoma, and then back to Missouri again. Realizing that the formula he had used in Kansas City, Harrisonville and Butler was a winner, Jack continued to refer to himself as S.V. “Jack” Clemens, and consistently scheduled his climbs in the afternoons at 2:30 or 3 o’clock, preferably on Saturday.

Arranging a visit to David A. Dunn, a friend from Joplin who had lived in California since about 1923, Jack jumped at the chance to bring his Human Fly act to the Los Angeles area. Shooting out Route 66 in January 1932, all the way to Riverside, California, he stayed with Dunn at 4030 Mulberry Street. Jack was eager for a new challenge. He soon found what he was looking for, and quickly got word to the papers that he was in town.

Jack embellished his story considerably while talking with the Riverside Daily Press. He beguiled them with razzle-dazzle. Obviously impressed, they called him “Jack Clemens, the world-famous ‘Human Fly’,” and revisited his Hotel Bray climb in Kansas City. Exuberantly, Jack declared he had scaled the Bray while blindfolded, presumably during the second climb in 1931.

The Daily Press printed their front-page story on January 21, 1932, under the headline “Human Fly Visits Riverside Friends.” While preparing the article, Jack and the reporter discussed the options available to a Human Fly in Riverside. Jack recognized that there were a few obvious candidates for him to consider climbing. The Mission Inn, an iconic hotel still operating in Riverside today, and the Citizens National Bank were proffered as possibilities. Smiling, Jack haughtily claimed that scaling the “Mission Inn, the tallest building in the city … would be no more difficult than going up the steps from the dining room to the bedroom in any two-story home in Riverside.”

Nonetheless, while it appeared that he was indifferent to the Mission Inn, Jack readily admitted that “his fingers and toes are tingling to conquer the Citizens National bank building,” which, he added, “looks like it might be tolerably hard with my eyes blindfolded as they were when I climbed the Bray hotel front.”

His boasting continued. Jack claimed he was “the only ‘human fly’ performing in the United States today.” Perhaps also attempting to impress David Dunn, Jack bragged that he was from Joplin, “home of Manager ‘Gabby’ Street of the St. Louis Cardinals champion baseball team of the world,” and also claimed that he was a personal friend of the baseball legend.

Of course, Jack hadn’t come all the way to California to climb for free. Concluding his calculated pitch, he urged the reporter to “just tell the Riverside folks if they feel like making it worth my while I’ll climb any building in the town with my eyes open or blindfolded, it makes no difference to me.”

Whether Jack made good on climbing either of these buildings in Riverside, or whether the “Riverside folks” put their hands deeply enough into their pockets to provide Jack with a payday, or even whether he was actually a friend of Gabby Street (doubtful), are all unknown. But Riverside was not his only stop during the trip. Just 17 miles away, Jack also brought his California climbing quest to Colton.

He turned up in Colton a week later. Jack’s arrival in the city was reported in the Colton Daily Courier on the Society Page under the headline, “‘Human Fly’ tackles Anderson Hotel here Saturday.” Still calling himself S. V. “Jack” Clemens, Jack followed his proven approach and scheduled his climb for 2:30 in the afternoon on Saturday, January 31, 1932. And, once again trying to differentiate himself from other Human Flies, Jack claimed he would go up the three-story structure blindfolded.

Encouraging readers to turn out for Jack’s planned climb, the Daily Courier went on to describe how “during the past several years” he had “been doing considerable climbing, furnishing many a thrill for spectators throughout the country.”

These are the only known locations Jack targeted for his act in California during this West Coast journey. Evidence suggests that he may have also visited Long Beach, laying plans to scale a building there as well. But no report has been found indicating which structure Jack may have intended to climb.

In any case, Jack and his new promoter did not remain in California for long. Two weeks after his visit to Colton, Jack was back in Missouri. And regardless of any promises he may have made to himself, or to Opal, or to little Virginia Belle, he quickly found himself in trouble again.

The Magic City

Jack veered from the straight and narrow early Sunday morning, February 14, 1932, when he was driving in Joplin with Vernon Jennings about half a mile east of Main Street. Somehow, Jack managed to crash into the back of a parked car on County Line, bringing their vehicle to an abrupt halt and severely lacerating Vernon Jennings’s chin.

Had they been out drinking together? How indeed does one run into a parked car? Did the timeframe of “early Sunday morning” indicate that Jack was trying to weave his car recklessly back home through the deserted streets of Joplin after drinking late into the night on Saturday with Jennings?

A quick delivery by ambulance to the hospital and Jennings was released the same day. Jack was uninjured, and as usual, shook it off, and somehow avoided the police. Soon, he was laying his next plans as a Human Fly.

By March, Jack was back out on Route 66 again, this time down to Tulsa, Oklahoma, nicknamed “The Magic City” due to its immense oil wealth. He targeted another hotel to climb, Hotel Brady. At eight stories, the Brady was of similar height to Hotel Bray in Kansas City, and significantly higher than Hotel Anderson in Colton had been.

Under the headline “Will Spurn the Stairs,” the Tulsa Tribune reported that “Brady hotel stairs and elevators will find themselves spurned by one man seeking to reach the roof of the eight-story building.” They also shared Jack’s bona fides as an actual steeplejack. “A member of the Painters Union, Clemens says he has been climbing difficult buildings about the middle-west and southwest for nine years, gaining his early experience in painting flagpoles and steeples.”

Jack stayed on script and announced he would tackle Hotel Brady on Saturday, March 5, 1932. The newspaper went on to inform their readers that he planned “to climb the main street side of the building beginning at 3 p.m.” his usual afternoon slot.

After Tulsa, Jack returned to Missouri. By the end of May 1932, he arrived in Springfield, another city along Route 66, purportedly to visit his sister. But while there, of course he attempted to persuade the city to turn out for his Human Fly act. He had finally dropped the “S. V.” and now presented himself simply as Jack Clemens. According to an article from the Springfield Morning News, Jack had already climbed in “Kansas City, St. Louis, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Omaha, besides a number of smaller cities.” They reported he planned to climb in Springfield on May 28.

The Morning News went on to say that “Clemens is married, but his wife has never watched him climb. She does not oppose the idea, but she does not have the nerve to watch him.” One wonders what Opal may have felt when they also reported that Jack “says his 4-year-old daughter is also learning to climb.” There has been no evidence found of any buildings scaled in Springfield, Missouri, during that visit or otherwise.

Midwest Mayhem

Returning triumphantly to Joplin at the start of summer, Jack could hold his head high again. He had apparently turned himself around and had glowing media coverage from California, Oklahoma and Missouri, to show for it. But old habits die hard.

At the end of July, Jack was drinking heavily again. And as had been demonstrated in the past, he had no compunction against driving while intoxicated. Slinging himself behind the wheel of his car on July 29, 1932, he took off down the road toward the center of Joplin, together with Charles Shaffer, also inebriated.

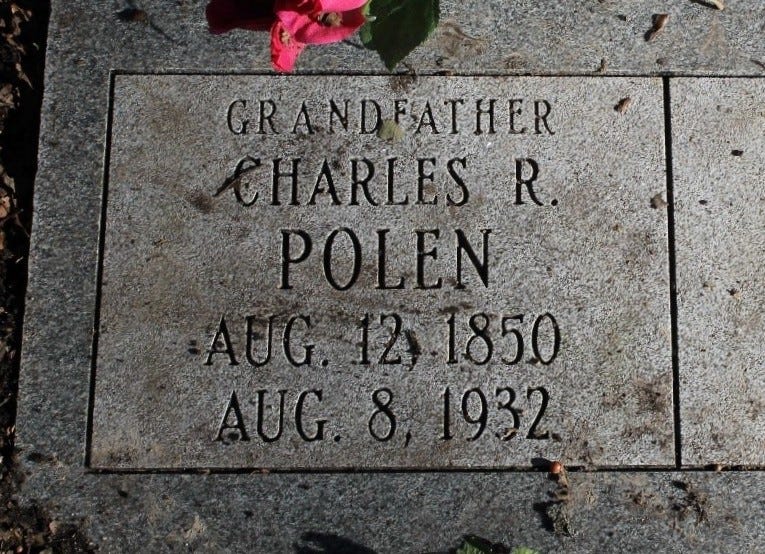

Barreling through the intersection at 10th and Joplin Avenue, Jack hit an 81-year-old street vendor named Charles Polen, who was just then crossing the street with his ice cream sandwich cart. The impact crushed Polen’s left leg.

Jack fled the scene of the accident on foot, leaving Shaffer behind on his own to deal with the consequences. However, Jack was quickly apprehended about a mile away by a motorcycle patrolman who nabbed him at Seventeenth and Ohio Avenue.

Polen was rushed to St. John’s Hospital, where doctors quickly determined he would have a better chance of surviving if they removed his shattered leg. Nevertheless, the amputation did not improve his condition. Polen died from his injuries ten days later at the hospital on August 8, 1932, just four days shy of his 82nd birthday. Until this moment, Jack had always been lucky enough to avoid critically injuring either himself or others involved in his several serious automobile accidents. Now a man was dead.

Charles R. Warden, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney, immediately charged Jack with driving while intoxicated, and soon announced he would add manslaughter and culpable negligence to the charges. Jack could not just shake off this transgression as he had each time in the past. No amount of charisma would help him now. He was facing years in prison, and his days as a Human Fly were at an end.

Incredibly, the charges of manslaughter and culpable negligence against Jack were dropped. The prosecutor had determined that the evidence was not strong enough to prove Jack could have avoided the accident even if sober. And, perhaps his father’s standing in the community as City Water Works Superintendent and President of the School Board of McClelland Park School in Newton County held some sway in reducing the charges. Nonetheless, Jack was still heading for prison on the drunk driving charge. Charles Shaffer, his traveling companion during the fatal collision, received a $10 fine for “drunkenness.”

On January 18, 1933, under the sub-headline “Human Fly to Jail,” the Joplin Globe reported that Jack would serve only sixty days in the county jail after pleading guilty to “driving a motor car while intoxicated.” Jack should have been locked up for a very long time. But amazingly, he had even been able to shake off the killing of an old man, a beloved ice cream vendor and church elder, who was widely known in Joplin. Jack had received yet another undeserved chance at resetting his own life, and now had sixty days of confinement to ponder how he might change for the better.

Jack was committed to the county jail at Carthage, Missouri, on January 27, to serve out his sentence of sixty days. Ironically, although Carthage was also a city on Route 66, for the coming two months, it was the end of the line for Jack. The door of his cell closed upon him. The Fly was trapped in a web of his own making … again. However, in another incredible stroke of luck, Jack was released after having served just 50 days, “for costs,” and left the jail a free man on March 18, 1933.

Could he get himself sorted out after this latest catastrophe? Or, was it just a matter of time before Jack was causing himself, and others, pain and sorrow once more?

Do unto others …

In 1933, it did indeed appear that Jack was determined to turn himself around again. No reports of wrongdoing have been found, nor any plans of climbs as a Human Fly. It seems that he simply reverted to his work painting signs and comported himself well-enough to stay out of trouble … for a while.

He also received a major job as a steeplejack in 1933. The largest zinc and lead mines in the United States were in Joplin, run by the Eagle-Picher Company, for whom Jack had worked in the past, including in Chicago. Mining these elements required an enormous amount of water at high pressure. A later report stated that he painted the 165-foot (50m) water tower on Smelter Hill at Eagle-Picher in Joplin in 1933, a prime example of steeplejack work, lending credence to the assumption that he was working that year rather than performing.

By the summer of 1933, Jack was living just south of Joplin at the Waterworks, where his father was superintendent. But fate continued to exact judgments against his previously odious behavior. At the end of June 1933, Jack reported his car stolen from Schifferdecker Park, leaving him a pedestrian. His car troubles would soon increase. However, Jack must have recovered his car, because he headed up Route 66 to visit the Chicago World’s Fair in the autumn of 1933. He returned home on October 18th.

By 1934, Jack had moved back into Joplin proper and was living at 1417 E. 12th, just a mile from where he had killed Charles Polen a year and a half before. However, his jobs regularly took him out of the city. In the Spring of 1934, Jack was on the road again, working as a sign painter. While plying his trade at the end of May just across the border in Kansas, he again became the target of others’ bad deeds.

On the 26th of May, Jack was driving on Route 66 near Galena, Kansas, when his car stalled. He was forced to leave the vehicle along the side of the road and go for help on foot. When he returned later, he found that his car had been completely stripped. The tires, wheels, battery, generator, and radiator had all been removed. The thieves even took the cushion from the rumble seat. What’s worse, they also stole Jack’s means of making a living, taking his sign-painting kit and brushes as well.

What was he to do? His car was useless now and the tools he used to make money were also gone. Instead of buckling down and rebuilding, he simply got himself into hot water again.

By the middle of August 1934, Jack apparently found work 200 miles from Joplin, in Jefferson City, Missouri, the capital city of the state. As usual, Jack also found trouble. Thinking he could score more than just a paycheck in Jeff City, Jack decided to add good old-fashioned grand theft auto to his bag of tricks. On August 16, obviously living by the rule, do unto others what has been done unto you, he was “caught pilfering a car.” The police were called, and Jack took off running.

He quickly ducked into a random house on Madison Street to hide. Jack couldn’t have made a worse selection of hiding places. The owner of the house, Officer George W. Vandament of the Joplin police force, was very surprised to see a stranger come rushing into his home. Calmly telling the intruder to wait until he could change his shoes, Vandament joined the chase as an astonished Jack Clemens dashed back out the door. But he was soon captured.

When he was taken into custody, Jack turned on the charm offensive. He told the officers that they were “all wrong about him.” Sharing stories of his exploits, Jack tried to win them over. He was a Human Fly, he said. Previously, he had “sent thrills tingling up and down the spines of the multitude while he climbed the walls of tall structures.” However, he also admitted that he had “relinquished this hazardous business to paint signs,” an obvious attempt to present himself as a hard-working, upstanding citizen.

The Cole County Prosecutor, Elliot Dampf, was having none of it. Jack was remanded to police custody, and, suggesting they suspected he was a fugitive from justice elsewhere, they sent Jack’s fingerprints to Washington D.C. A preliminary hearing was scheduled for the following week. Not only was he expected to “explain his interest in automobiles belonging to others,” but to make matters worse, Jack was also being charged with “entering and breaking into a house” for his attempt to hide from the law in Officer Vandament’s home.

During the hearing, Prosecutor Dampf could not resist serving Jack with a cynical, left-handed compliment. “You’re a lucky guy,” he said. “Of all the 5,000 houses in Jefferson City you had to pick out a policeman’s house to run into.” Of course, bad luck was also luck, and Jack knew he had been bested. He “smiled ruefully” at the wry comment.

Humiliated, but unlikely humbled, when he finally freed himself from Jefferson City, Jack shook off his bad luck as usual, and then took off for Texas to let things cool down. What he did there, and whether he pursued work as a steeplejack, or a sign painter, or even as a Human Fly is unknown. But while he was in Texas, something about the state appealed to him. And even after he repatriated himself to Missouri, thoughts of returning to the Lone Star State stayed with him.

Climbing back up

The summer of 1935 brought Jack back to Joplin, but Opal was living in Kansas City with her mother. Undoubtedly, she had grown tired of Jack’s antics. It must have been a constant worry for her. What kind of pain would her husband cause next, and to whom? What trouble would he get himself into? Would he end up in jail again? And, for how long? Could he ever straighten up and finally leave his drinking and his Human Fly pursuits behind him?

But perhaps Opal also harbored a deep, unspoken thought that a dramatic end for Jack, hurtling headlong into the ground from the precipice of a building ledge, would be better for everyone, even him. And at the same time, it would free her from the suffering and uncertainty she had been forced to endure for so long.

For now, Jack returned to his work as a steeplejack. He jumped at the chance to paint the water tower on Smelter Hill at the Eagle-Picher mines for a fifth time. The Joplin Globe informed the city of Jack’s impending effort, complete with start date and time. Obviously the painting of this 165-foot-high (50m) structure was still reason enough to attract spectators to watch him work. As usual, Jack didn’t stick around for long, and when he was finished, he headed back out on the road. Having suppressed his desire to perform for the last couple of years, it was time to flex his stubby fingers as a Human Fly again.

In May of 1936, Jack had found his way to Muscatine, Iowa. Using his charm and proven formula, he was able to secure a report in the local newspaper, the Muscatine Journal and New Tribune, and he went through all the tactics he had used in the past. Jack even stuck with the same script he had followed in Kansas City a few years before, as he again looked for a “suitable structure on which to strut his prowess.” If an appropriate building was found, the Journal and Tribune reported, he would climb it on Saturday afternoon, May 9.

Readers were told that Jack was “one of those defiers of the dizzy heights going under the nom de plume of ‘The Human Fly.’” The article called him the “red-headed boy from Joplin” who claimed to be, “one of the few remaining ‘Human Flys’ in the business.” Perhaps thinking back to the droll humor of Prosecutor Dampf in Jefferson City, Jack also quipped that “he hopes business is not ‘dropping off.’” Opal may have had a different opinion.

In the end, Jack found his building. And, deviating from his usual script, he announced he would climb the Hotel Grand in Muscatine on the evening of Saturday, May 9, 1936, at 6pm.

The three-story building was of similar height to the Hotel Anderson in Colton, California. Jack made no mention of whether he intended to climb blindfolded or not.

Rejuvenated once more by returning to his role as a Human Fly, Jack stayed in character that year. By the middle of November 1936, he had followed Route 66 to warmer weather in the west once again. Jack had to share the road this time. Others were also looking for new opportunities. Tens of thousands of Okies, fleeing the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma, also traversed Route 66, the Mother Road, headed for a better life as farmhands in California. But Jack did not thrust his hands into the ground to make a living, and kept his eyes turned upward as he grappled toward the sky.

Somehow, Jack landed a job performing with the Burke Shows Carnival in Yuma, Arizona. The Yuma Sun reported on his arrival, and Jack amplified his narrative once more. Whereas in Muscatine he had claimed to be “one of the few remaining ‘Human Flys [sic],’” now to the Yuma Sun, Jack simply proclaimed again, as he had in California, that he was “the only living human fly.”

His tall tales continued. Jack asserted that “the highest he has climbed is to the top of the 22 story Mayo Building in Tulsa, Oklahoma.” And, he declared, he had “climbed to the top of the Connor Hotel in his native Joplin,” recalling the feats of Harry Gardiner and George Polley before him. Whether either of these claims is true cannot be verified with any known newspaper reports.

In addition to the stunts he performed for the Burke Carnival, the Sun reported that Jack would also appear November 27th at the Rodeo in Chandler, Arizona, just outside of Phoenix. According to the coverage of the event, even Tom Mix, the most famous star of movie westerns, was expected to attend. The sold-out rodeo seated 6000. No doubt, Jack’s daredevil act found a ready reception amongst the other hazardous events at the show.

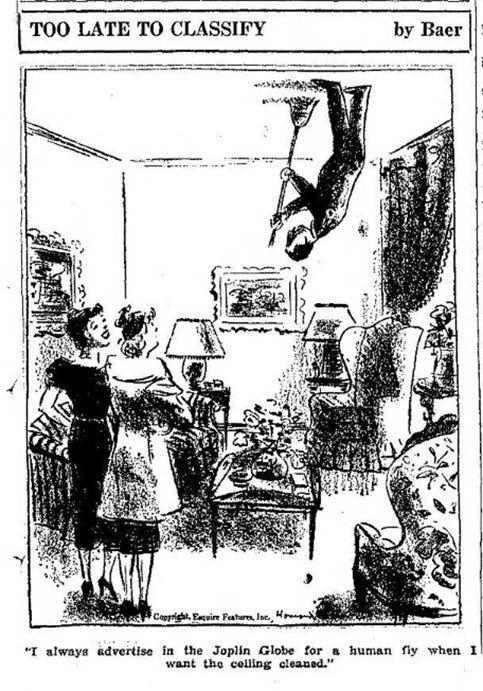

On December 22, 1936, as Jack was moving on from his work in Arizona, the Joplin Globe ran a comic that took a light-hearted look at the Human Fly. During the Great Depression, the cultural phenomenon of the Human Fly was slightly less ubiquitous than it had been in the 1920s. Nonetheless, the exploits of these daredevils still resonated in the imaginations of people and cities across the United States, and poking fun at them from time to time also provided a well-needed laugh.

The unlikely juxtaposition of risking one’s life climbing a building with tackling a mundane housecleaning chore no doubt brought the intended chuckle. But the danger inherent in pursuing such a profession would be made abundantly clear in Tennessee in the coming year, at ultimate expense of one of the best-known Human Flies in the country.

Last Hurrah

After his exhibition work in Arizona came to an end, Jack found employment as a steelworker during the first five months of 1937. But by the middle of May, he was back in Kansas City, Missouri, looking for work, and also looking for Opal. Moving into quarters just a couple of blocks away from where Opal’s mother Ida Belle Turnow kept her house downtown, Jack placed a “Situations Wanted” ad in the Kansas City Star that ran on May 13th & 14th.

This small ad was trivial compared to the impressive photo depicting Jack climbing the face of Hotel Bray that had been featured in the same newspaper only six years before. Reverting once more to his roots as a steeplejack, it seemed that Jack’s days as a Human Fly were finally over. But still, he wanted more.

His job as a steelworker had likely provided a bit of the thrill he desired, and by specifically seeking “high painting” in his ad in the Star, it was obvious that Jack would not be satisfied with working while his feet were safely on the ground. The temptation of climbing for a crowd, and for the quick money he could get for a few hours’ work, were irresistible. Perhaps also now finding Opal fully capable of resisting his charms, two weeks later, Jack was on the road again.

At the beginning of June of 1937, he brought his “only living human fly” schtick to Omaha, Nebraska. The Omaha World Herald reported on Jack’s presence under the headline “Human Fly Here.” But the reporter wasn’t buying his “only living human fly” swagger and firmly placed “(according to himself)” behind the claim in the article. Nonetheless, Jack was sticking to script, including his financial overture. The article mentioned that he “expects to contact persons interested in sponsoring a climb.”

Reflecting on the dichotomy of Jack's career, and his obvious attraction to “the easy money that goes with the courtship of death,” the report revealed that he was a “sign painter by trade, but a human fly by choice.” The story also claimed that this was his first time in Omaha. However, back in 1932, Jack stated that he had already climbed in the city. Regardless of whether it actually was his first visit, he would never return. No report has been discovered about Jack’s planned climb in Omaha, nor which building he may have intended to tackle.

But much has been written about the final climb of well-known Human Fly Henry “Daredevil” Roland, which took place a few months after Jack visited Omaha. On October 7, 1937, at the Ottway County Fair, in Greenville, Tennessee, Roland thrilled the crowd as he climbed to the top of a 90-foot (27m) ladder, and then further up a 20-foot (6m) pole affixed atop the ladder. Balancing upside down on his hands, Roland then rocked back and forth as he swayed to and fro upon the pole, six feet (2m) to either side.

On the way back down for his finale, Roland had attached a trapeze to the ladder, 62 feet (19m) off the ground. He planned to do a forward somersault from the ladder, catching himself by his ankles on the bar of the trapeze. But just as Roland performed his flip, a gust of wind blew the trapeze away from him and he could only catch it with one of his feet. He plummeted into the ground and died on impact.

The price of being a Human Fly was all too often paid with one’s life. And Jack had been fortunate until now not to have met his end by tumbling back to the earth. But death can also come for a Human Fly when he believes he is safely on the ground. And, of course, even a Human Fly has his feet firmly planted most of the time.

I heard a Fly buzz …

After Omaha, Jack was back in Joplin. Increasingly, he recalled his time in Texas, and the opportunities he might find there. Near the beginning of November 1937, Jack decided to move to Dallas. He took his wife with him. But he also took his troubles. After arriving in Dallas, they only stayed in the city for a few weeks before relocating to Fort Worth, Texas, just 30 miles away.

Finding rooms to rent downtown, they moved into the home of Arthur and Addie Washburn at 214 North Florence Street. Jack was working as a sign painter again, and doubtless scheming to thrill the locals with his Human Fly act. But he was also drinking heavily. After only a week in Fort Worth, Jack was completely out of control. In the afternoon of the 9th of December, his landlord Washburn heard him shouting and acting “very wild.”

A doctor was called and attended to Jack around 6pm. But his loud, frantic behavior did not subside, and Washburn warned him that if he didn’t “quiet down,” he would have to call the police. Jack shouted out, “No police stuff in mine” and then, inexplicably, “he lowered his head and rammed it through a glass door pane.” Washburn called the police. Jack was arrested at 10:10pm.

Hauled to the City Jail, Jack refused to provide his name, “and he was booked as a John Doe.”

The City Jail had recently been moved from the Old City Hall, with the cells being cut out, moved and reassembled in the basement of the Old Post Office in Fort Worth. The City Jail re-opened under the post office November 23, 1937, just a couple of weeks before Jack was brought in and booked. Ironically, the Old Post Office was precisely the kind of structure that Jack would have targeted for climbing in better days, aiming for the top. But now, he was imprisoned beneath it.

Jack’s wild behavior continued, so he was placed in a cell by himself, away from the other inmates. Finally, he calmed down. At about 3:15am, Virgil Osborne, the turnkey of the jail, checked on the prisoners and saw Jack sleeping in his cell. When Osborne took another look about 45 minutes later, he could tell there was something wrong. He found Jack Clemens dead at 4am and alerted his superiors, who arrived to investigate the scene.

“City physician Houston Terry examined the body, Justice of the Peace Hal P. Hughes conducted the inquest. Hughes, after he, Homicide Officer Howerton and Physician Terry located [Jack’s] widow and talked to her, returned a verdict of death from acute alcoholism.”

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 10, 1937

When so many other Human Flies had given their lives dramatically plunging headlong into the ground, Jack had given his to the bottle … or, so it seemed. The official cause of death, type-written on his death certificate, read, “Deceased came to his death from Acute Alcoholism,” and was endorsed with the signature of Justice of the Peace Hughes.

But there’s a different story about Jack’s death still told by his family, and I am inclined to believe it’s true. While there is no doubt that Jack abused alcohol regularly, many times with disastrous consequences, the events of his last day were very odd, even for him.

As the family relates the story, during his travels in the last weeks before he died, Jack had been bitten by a dog. And, they go on to explain, on that very last day of his life in Fort Worth, Jack was not dying from acute alcoholism, he was in the death throes of acute rabies.

While alcohol can drive a man to do outrageous things, shoving his head through a glass pane in a door was a highly peculiar act, even for a liquored-up Jack Clemens. And, indeed, the frenzied, erratic behavior he displayed the day he was arrested was consistent with the description of how a human infected with rabies might behave.

According to the United States Center for Disease Control (CDC):

The first symptoms of rabies may be similar to the flu, including weakness or discomfort, fever, or headache. There also may be discomfort, prickling, or an itching sensation at the site of the bite. These symptoms may last for days.

Symptoms then progress to cerebral dysfunction, anxiety, confusion, and agitation. As the disease progresses, the person may experience delirium, abnormal behavior, hallucinations, hydrophobia (fear of water), and insomnia. The acute period of disease typically ends after 2 to 10 days. Once clinical signs of rabies appear, the disease is nearly always fatal.

Taking the above timeline into account, with the acute period of a rabies infection and its associated “abnormal behavior” ending in death after 2 to 10 days, this could also explain Jack’s abrupt move from Dallas to Forth Worth. Perhaps he had already started exhibiting the bizarre symptoms of a rabies infection and was turned out of his rooms in Dallas. An advanced infection would also explain how he suddenly died in Fort Worth only a week later. It’s a compelling story.

Moreover, if Jack had simply been on a drunken rampage that delirious day of December 9th, why would a doctor have been called to attend to him? But, even if the doctor could have determined that Jack was a victim of rabies, by then, it was way too late to save him.

Regardless of the cause, Jack Clemens, Human Fly, was dead at the age of 32. But his story was not quite over yet.

Final Goodbyes

The day after Jack died and the official inquest had been completed, his body was sent to Joplin for burial. The Joplin Globe, having reported on so many of Jack’s shenanigans over the years, both as a Human Fly, and also as a menace to society, had one last story to run about him. The day after Jack’s body was sent to Joplin, the Globe printed his obituary.

It is doubtful that anyone was surprised he had died so young. Jack led an extremely fast life. When he wasn’t in trouble with the law, he was hanging off the sides of buildings. While Jack’s death must have been an extremely sad occasion for his parents James and Mollie Clemens, and certainly his brothers and sisters fondly remembered some of the good times they had shared with him over the years, surely Opal was torn.

Silently, she must have breathed a sigh of relief that Jack’s wild antics and unpredictable lifestyle were at an end. Nevertheless, the father of her child was gone. And Opal knew from experience exactly what it was like to grow up without a father. Virginia Belle would turn just 9 years old at her next birthday a few weeks later, the same age Opal was when her own father died.

Tuesday, December 14, 1937, Jack’s funeral was held at 10:30 in the morning at the Hurlburt Chapel in Joplin. Elder Oscar Karlstrom, pastor of the Reorganized Church of the Latter Day Saints where the Clemens family attended, officiated the service. Jack was buried the same day in the Forest Park Cemetery in Joplin.

Questions & Quandaries

Even now, 86 years after he was found dead in his jail cell in Texas, puzzling questions about Jack’s death still abound.

In Fort Worth, two articles in the Star-Telegram reported on his wild behavior and his death, and mentioned “Mrs. Clemens” several times without listing her first name. However, when his death certificate was drawn up, strangely Jack’s wife was recorded as Mary Bell Clemens. Who was she? Did Opal Gladys Clemens provide a false name to the authorities? If so, why? Or, had Jack and Opal split up, and Jack taken a new wife named Mary Bell, and it was she who was dealing with his death? The stories in the newspaper also made no mention of a child being with them, a salient detail. If Opal was with Jack, then was Virginia Belle Clemens presumably with her grandmother in Kansas City still?